Growing up, I always thought weather was just something that happened. As a kid, I’d play in the rain, jump around in puddles, make snowmen. What an arrogant fool I was, unaware of the power and majesty of the elements. I was even more enthralled by the mysterious man on the screen who commanded them. Watching him then, I did not know his name, nor that he would plant in me a seed that would be watered with my own tears, with a high of 76 and a low of 57. I may have started as a naive Weatherboy, but trial and hardship have molded me into a fierce and ferocious Weatherman.

People call me a meteorologist, but I’ve never liked those fancy ten-dollar lawyer words. Weathermanning isn’t something that can be taught in a classroom at a prestigious university. I should know: I’ve never even seen a college. Weathermanning is taught in the real world, with night classes at the school of hard knocks and an internship in the streets.

Some think being a weatherman is easy. They say things like “It’s just pointing at a screen,” and “They’re wrong half the time,” and “I don’t care if you’re with your son, you’re drunk and you need to leave the zoo.” I don’t even hear them anymore. I cut out the part of me that hears criticism long ago. Ask any of my ex-wives.

The truth of the matter is my rise to the top was nothing short of a living nightmare. It was a slow crawl through the barbed wire of embarrassment and over the broken glass of not being taken seriously by potential sexual partners. My very first day, I, like a common idiot, mistook sleet for wintry mix. Distraught, I left work and yelled at my cat for seven hours. Little did I know, only a few weeks later, I was to be yelled at by the cat known as Fate.

4th of July weekend, 1989. We had a high-pressure zone moving in off the coast, just itching to bump uglies with a slow-moving cold front from the north. These two were going to smash together like teenagers whose parents were out of town — enthusiastically and awkwardly. I had to face the nation, or at least the residents of Sarasota county, and inform them that the fireworks would have to be canceled that year. I might as well have been asked to tap dance backwards into a minefield. Everyone was convinced the storm was coming, but not me. They encouraged me to “Look at the radar,” and “Do what we’re paying you to do, goddammit.” To me, their words sounded like words, but words I didn’t want to listen to.

Ten minutes to air, I discovered that a pocket of swamp gas released overnight by a meth lab explosion had pushed the cold front off course. The clouds parted and I emerged victorious. The city had already canceled the fireworks the day prior, but I was vindicated. In that moment, I learned what it feels like when God cums.

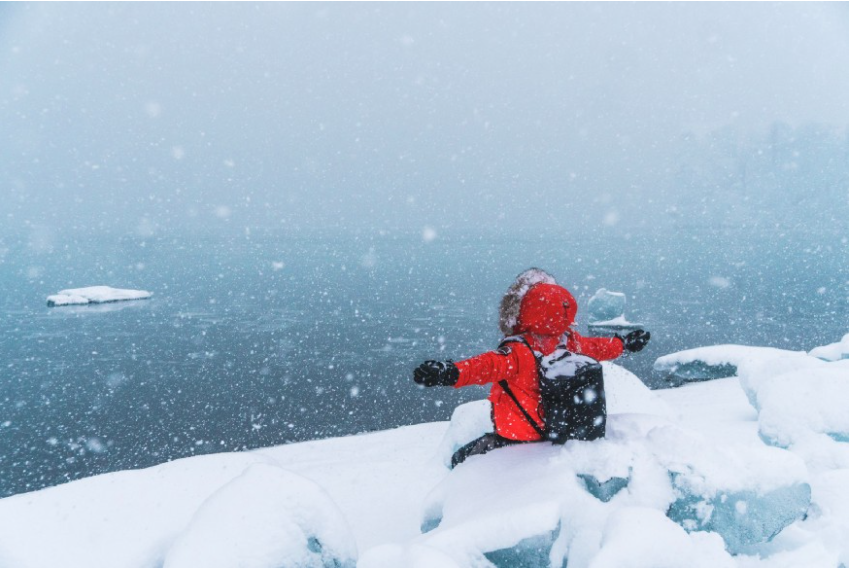

Now look at me. Lord of sunshine, emperor of thunder, harbinger of storms, and lead-in to sports. Many say that I only report the weather. But that’s what a meteorologist does. I’m a weatherman. I AM the weather. And when duty calls, when there’s a bomb cyclone or a microburst, I strap on my tall rubber boots and drape myself in my yellow raincoat with the flappy hood, and I rush into danger. Most people have never seen the eye of a hurricane. I haven’t either, but I’ve stood outside in the rain to let people know it’s raining.

So the next time you’re out, look directly up at the sun and thank me for allowing it to shine. Without me, the rain, wind, sun, and snow are just phenomena, bereft of any meaning and direction. But in my hands they become weather, always lurking in the distance waiting to either bless your weekend or make it mildly inconvenient. In antiquity, I would have been called a shaman, a rainmaker, an extension of the holy realm. These days, I’m simply “Chet Blimpton with the weather.” I, and I alone, am with the weather, and the weather is with me.